Escogitò per primo la nozione di buco nero

Alcune fonti parlano del reverendo Michell, pastore anglicano, come di un parroco di campagna interessato alla scienza solo per diletto e imbattutosi nell’idea dei buchi neri quasi per caso. La verità è ben diversa: Michell era uno scienziato che fu eletto membro della Royal Society nel 1760, prima di diventare sacerdote. Egli era noto per avere studiato il disastroso terremoto che distrusse Lisbona nel 1755. Michell stabilí che il sisma era stato causato da una perturbazione della crosta terrestre sotto l’Oceano Atlantico, e oggi è considerato il padre della scienza della sismologia.

Non si conoscono il luogo e la data di nascita esatti di Michell, ma sappiamo che proveniva dal Nottinghamshire, dove nacque probabilmente nel 1724. Studiò all’Università di Cambridge e si laureò nel 1752, diventando prima fellow al Queen’s College e poi, nel 1762, Woodward professor di geologia. A quel tempo era comune fra gli accademici dell’università (che aveva origini ecclesiastiche) prendere gli ordini sacri, non necessariamente con l’intenzione di lavorare nella Chiesa; ma nel 1764, un anno dopo aver conseguito il titolo di Bachelor in teologia, Michell lasciò l’università per diventare parroco a Thornhill, nello Yorkshire.

Ciò non gli impedí di continuare a nutrire un vivo interesse per la scienza, e la sua canonica fu frequentata regolarmente da Wilhelm Herschel. Nel 1767 Michell pubblicò un saggio in cui sosteneva che in cielo ci sono troppe stelle binarie per considerarle come semplici giustapposizioni di stelle lontane fra loro lungo la linea visuale, e che alcune di tali stelle doppie dovevano essere associate fisicamente. Fu anche il primo a compiere una stima realistica della distanza di una stella. Basandosi su un ragionamento fondato sulla luminosità apparente di Vega, calcolò che la stella dista da noi circa 460.000 volte piú del Sole, distanza che corrisponde al 25% circa del valore attualmente accettato.

Michell fece ricerche importanti anche sul magnetismo (prima di lasciare Cambridge), e a Thornhill inventò uno strumento noto come bilancia di torsione che poteva essere usato per misurare la grandezza esatta di forze molto piccole. Egli intendeva usarlo per misurare la grandezza della gravità attraverso la forza esercitata da una grande massa su un bastoncino, ma morí prima di poter eseguire questo esperimento. Esso fu compiuto, usando la tecnica di Michell, dal suo amico Henry Cavendish (1731-1810), brillante scienziato enciclopedico inglese, e i risultati furono pubblicati nel 1798. Il Cavendish Laboratory di Cambridge, fondato nel 1871, è stato intitolato a lui.

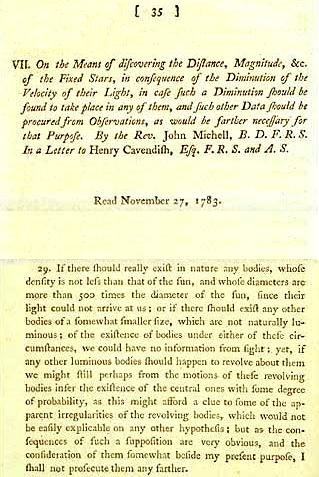

Ma quella che oggi sembra l’idea piú geniale e lungimirante di Michell non è spesso neppure menzionata nelle opere piú importanti. Il primo accenno a quelle che egli chiamò dark stars (stelle buie) è contenuto in una relazione alla Royal Society del 1783, letta per suo conto da Cavendish. Era una discussione sorprendentemente dettagliata sui modi per determinare le proprietà delle stelle, comprese la loro distanza, grandezza e massa, attraverso una misurazione dell’effetto gravitazionale esercitato sulla luce emessa dalla loro superficie. Tutto si fondava sull’idea di Newton che la luce fosse composta da piccole particelle (note talvolta come corpuscoli), e sulla supposizione che «le particelle della luce» fossero attratte dalla gravità «nello stesso modo di tutti gli altri corpi noti».

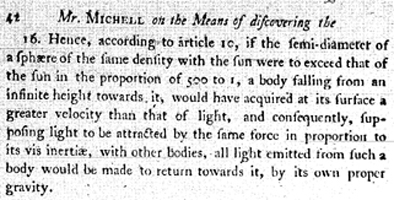

Alcuni stralci dell'opera di John Michell dove, nel 1783,

descrisse per primo il concetto di buco nero.

Il testo venne pubblicato nelle Philosophical Transactions of the Royal

Society of London (vol. 74 (1783), 35)

Michell si rese conto che, se una stella fosse stata abbastanza grande, quella che noi chiamiamo la velocità di fuga dalla sua superficie avrebbe superato la velocità della luce. Fra i molti ragionamenti dettagliati esposti nel suo saggio, per molto tempo dimenticato ma oggi diventato famoso, egli sottolineò che, di conseguenza:

«Se in natura dovessero esistere corpi di densità non minore di quella del Sole, il cui diametro fosse piú di 500 volte maggiore, non potremmo averne alcuna informazione visiva... dato che la loro luce non potrebbe pervenire fino a noi; e tuttavia, se un qualche altro corpo luminifero dovesse compiere le sue rivoluzioni intorno a un tale corpo, noi potremmo forse inferire con qualche probabilità, dal moto di rivoluzione di tali corpi orbitanti, l’esistenza dei corpi centrali, poiché questa potrebbe fornire indizi su irregolarità apparenti dei corpi orbitanti che non sarebbero facilmente spiegabili con alcun’altra ipotesi».

Una sfera 500 volte maggiore del Sole sarebbe grande pressappoco come il sistema solare, cosicché il tipo di stella buia considerata da Michell è molto simile al tipo di buco nero che si pensa si trovi al centro dei quasar.

L’idea di Michell di identificare la presenza dei buchi neri in sistemi binari attraverso la loro influenza gravitazionale sulle orbite delle loro campagne corrisponde esattamente al modo in cui fu identificato, nel 1972, il primo buco nero nella Galassia, il Cygnus X-1, 189 anni dopo la relazione di Michell alla Royal Society.

Michell morí a Thornhill il 9 aprile 1793.

Cfr. GRIBBIN J., voce Michell John (1724-93), in Enciclopedia di Astronomia e Cosmologia, Garzanti, Milano, 1998, 259-260 e 314-315.

Extract from the 1784 article by John Michell, in which

the

concept of a black hole was first formulated

JOHN MICHELL AND BLACK HOLES

[ Original text from: http://www.amnh.org ]

A black hole is a volume of space where gravity is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape from it. This astonishing idea was first announced in 1783 by John Michell, an English country parson. Although he was one of the most brilliant and original scientists of his time, Michell remains virtually unknown today, in part because he did little to develop and promote his own path-breaking ideas.

Michell was born in 1724 and studied at Cambridge University, where he later taught Hebrew, Greek, mathematics, and geology. No portrait of Michell exists, but he was described as “a little short man, of black complexion, and fat.” He became rector of Thornhill, near Leeds, where he did most of his important work. Michell had numerous scientific visitors at Leeds, including Benjamin Franklin, the chemist Joseph Priestley (who discovered oxygen), and the physicist Henry Cavendish (who discovered hydrogen).

The range of his scientific achievements is impressive. In 1750, Michell showed that the magnetic force exerted by each pole of a magnet decreases with the square of the distance. After the catastrophic Lisbon earthquake of 1755, he wrote a book that helped establish seismology as a science. Michell suggested that earthquakes spread out as waves through the solid Earth and are related to the offsets in geological strata now called faults. This work earned him election in 1760 to the Royal Society, an organization of leading scientists.

Michell conceived the experiment and built the apparatus to measure the force of gravity between two objects of known mass. Cavendish, who actually carried out the experiment after Michell’s death, gave him full credit for the idea. The measurement yielded a fundamental physical quantity called the gravitational constant, which calibrates the absolute strength of the force of gravity everywhere in the universe. Using the measured value of the constant, Cavendish was able for the first time to calculate the mass and the average density of the Earth.

Michell was also the first to apply the new mathematics of statistics to astronomy. By studying how the stars are distributed on the sky, he showed that many more stars appear as pairs or groups than could be accounted for by random alignments. He argued that these were real systems of double or multiple stars bound together by their mutual gravity. This was the first evidence for the existence of physical associations of stars.

But perhaps Michell’s most far-sighted accomplishment was to imagine the existence of black holes. The idea came to him in 1783 while considering a hypothetical method to determine the mass of a star. Michell accepted Newton’s theory that light consists of small material particles. He reasoned that such particles, emerging from the surface of a star, would have their speed reduced by the star’s gravitational pull, just like projectiles fired upward from the Earth. By measuring the reduction in the speed of the light from a given star, he thought it might be possible to calculate the star’s mass.

Michell asked himself how large this effect could be. He knew that any projectile must move faster than a certain critical speed to escape from a star’s gravitational embrace. This “escape velocity” depends only on the size and mass of the star. What would happen if a star’s gravity were so strong that its escape velocity exceeded the speed of light? Michell realized that the light would have to fall back to the surface. He knew the approximate speed of light, which Ole Roemer had found in the previous century. So it was easy for Michell to calculate that the escape velocity would exceed the speed of light on a star more than 500 times the size of the Sun, assuming the same average density. Light cannot escape from such a body, which would, therefore, be invisible to the outside world. Today we would call it a black hole.

Michell got the right answer, although he was wrong about one point. We now know, from Einstein’s relativity theory of 1905, that light moves through space at a constant speed, regardless of the local strength of gravity. So Michell’s proposal to find the mass of a star by measuring the speed of its light would not have worked. But he was correct in pointing out that any object must be invisible if its escape velocity exceeds the speed of light. This concept was so far ahead of its time that it made little impression.

The idea of black holes was rediscovered in 1916, after Einstein published his theory of gravity. Karl Schwarzschild then solved Einstein’s equations for the case of a black hole, which he envisioned as a spherical volume of warped space surrounding a concentrated mass and completely invisible to the outside world. Work by Robert Oppenheimer and others then led to the idea that such an object might be formed by the collapse of a massive star. The term “black hole” was itself coined in 1968 by the Princeton physicist John Wheeler, who worked out further details of a black hole’s properties.

The most common black holes are probably formed by the collapse of massive stars. Larger black holes are thought to be formed by the sudden collapse or gradual accretion of the mass of millions or billions of stars. Most galaxies, including our own Milky Way, probably contain such supermassive black holes at their centers.

Astrophysical theory allows black holes to come in many sizes, and the size of a black hole is simply proportional to its mass. Thus, a black hole with the mass of the Earth would be about an inch across, one with the mass of the Sun would be a few miles across, and one with the total mass of the Milky Way Galaxy would be about a light-year across. The larger a black hole, the lower its average density, and it is conceivable that our entire observable universe is a supermassive black hole within a larger universe.

Michell suggested that we might detect invisible black holes if some of them had luminous stars revolving around them. In fact, this is one method used by astronomers today to infer the existence of black holes. We have observed numerous systems in which matter, whether gas clouds or entire stars, is moving so fast that only the concentrated mass of a black hole could be responsible for it.

While black holes strongly influence the space immediately around them, the notion that they behave like cosmic vacuum cleaners, sweeping up everything in the neighbourhood, is a popular fallacy. If the Sun were somehow collapsed to form a black hole, the orbital motion of the planets would be unaffected. The central mass would remain the same, so the planets would feel the same gravity as before. What distinguishes a stellar black hole is its very small size and high density. This allows other bodies to get very close to the center of mass, where the gravity is extremely intense. But it does not increase the pull of gravity far away from the mass.

When John Mitchell conceived of black holes in 1783, very few scientists in the world were mentally equipped to understand what he was talking about. It is not surprising that the concept sank into complete obscurity and had to be rediscovered in the twentieth century.